More Information on Enforcement Actions Against DTE Shenango

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Allegheny County Health Department have taken several enforcement actions against DTE Energy relating to air emissions from its Shenango coke plant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The Consent Orders contain some provisions that reflect the types of structural changes needed to generate significant reductions in air emissions. The following links contain documents relating to these enforcement actions.

While the facility closed in 2016, the enforcement history provides a context for evaluating the compliance of other coke oven operations with the Clean Air Act.

1. Title V Operating Permit.

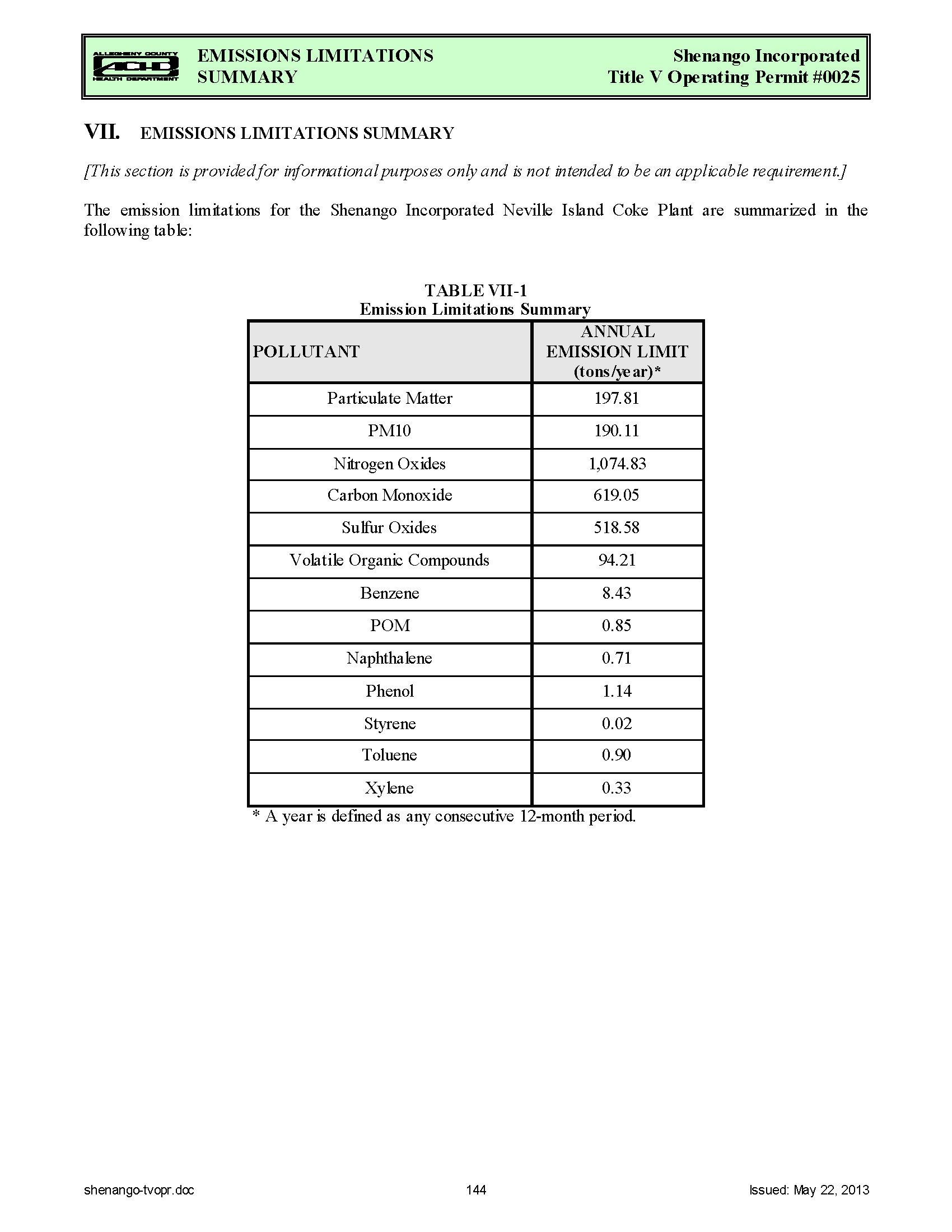

Even if it had operated in compliance with the conditions of its Title V permit, the facility’s air emissions were significant. The following table sets forth the allowable emissions for the facility.

Emissions Limitations Summary

| POLLUTANT | ANNUAL EMISSION LIMIT (tons/year)* |

| Particulate Matter | 197.81 |

| PM10 | 190.11 |

| Nitrogen Oxides | 1,074.83 |

| Carbon Monoxide | 619.05 |

| Sulfur Oxides | 518.58 |

| Volatile Organic Compounds | 94.21 |

| Benzene | 8.43 |

| POM | 0.85 |

| Naphthalene | 0.71 |

| Phenol | 1.14 |

| Styrene | 0.02 |

| Toluene | 0.90 |

| Xylene | 0.33 |

* A year is defined as any consecutive 12-month period.

Of particular concern were the emission of 197.11 tons per year of particulates (including pollutants known to cause premature death), 1,074.83 tons per year of nitrogen oxides (precursors to the formation of particulates and ozone), 518.58 of sulfur dioxide (precursors to the formation of particulates), 94.21 tons per year of volatile organic compounds (precursors to the formation of particulates and ozone), and 8.43 tons per year of benzene (a known carcinogen).

This information is recorded on page 144 of the Title V permit:

Source: Shenango Title V Operating Permit

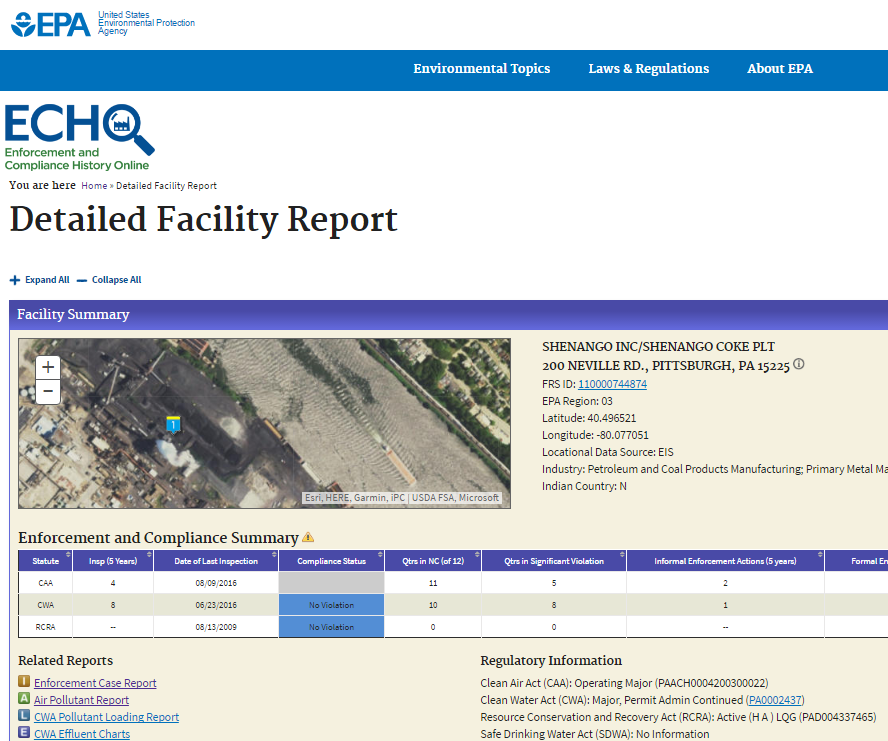

2. Compliance History

Enforcement actions typically take the form of fines and consent orders. The effectiveness of enforcement depends on the willingness of an agency to require compliance with the requirements of environmental laws and regulations.

During the last five years, the facility was the subject of 31 enforcement actions under the Clean Air Act, for which it was assessed $1,757,850 in penalties. This included violations relating to visible emissions, coke oven emissions, and fugitive emissions.

Source: EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online,

3. Consent Order and Agreement (June 19, 2012)

In June 2012, the Allegheny County Health Department entered into a consent order with the operator of the facility. The purpose of this consent order was to preserve the rights and obligations of the parties relating to repairs and maintenance, following the termination of a 2000 Consent Decree.

Although the consent order prohibits the release of soaking emissions from a standpipe cap opening which exceed 20% opacity, it allows for an exclusion from this limit for two minutes after a standpipe cap is opened. Soaking emissions refer to “uncombusted emissions from an open standpipe which has been dampered off in preparation of pushing the coke mass out of the oven and shall end when pushing begins, i.e., when the coke side door is removed.” The consent order required two soaking observations at the Coke Oven Battery each day.

The consent order also prohibited the operation of any source in such a manner that unburned Coke Oven Gas is emitted into the open air. Daily average sulfur compounds were limited to 34 grains per hundred dry standard cubic feet of Coke Oven Gas.

The facility was allowed a certain number of outage hours for repair and maintenance at the Desulfurization Plant.

The consent order contained requirements relating to the Continuous Emissions Monitoring device required by the facility, and monitoring in case of a failure of the device. It included requirements relating to the particular sulfur compounds to be monitored, and how calculations were to be performed. There were also recordkeeping and record retention requirements. The facility was required to file quarterly reports relating to daily average sulfur compounds.

While the consent order did not impose civil penalties, it prescribed stipulated penalties in the event that the facility did not comply with its requirements, including the soaking requirements.

4. Consent Decree (federal, state, and county, November 6, 2012)

In 2012, the United States, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and the Allegheny County Health Department filed a Complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania, seeking civil penalties for violations of the Clean Air Act and an injunction against further violations.

The plaintiffs asserted five claims relating to visible emissions from charging, door areas, charging ports, offtake piping, and pushing. It also asserted claims for violations of opacity limits at the combustion stack and limits on flaring, mixing, and combustion of coke oven gas.

Source: United States of America and Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and Allegheny County v. Shenango Incorporated, Civil Action No. 12-1029, entered November 6, 2012

The parties ultimately resolved this litigation through a Consent Decree filed on November 6, 2012. This Consent Decree was one of a series of Consent Decrees entered in 1993, 1999, 2000.

One of the problems contributing to the facility’s inability to meet emissions limitations was the occurrence of frequent operational difficulties with recently-installed Sulfiban and SulFerox units, which had been installed as sulfur removal technologies for Coke Oven Battery S-1.

With respect to compliance requirements, the facility was required to comply with county regulatory standards for particulates and opacity. It was also required to implement an Elevated Opacity Response Protocol, a Battery Heating Protocol, and a Coke Oven Proactive Maintenance Program. It was required to completed end flue repairs and ceramic welding on ovens and walls according to a schedule.

With respect to monitoring requirements, the facility was required to operate its transmissometer in accordance with federal regulations and relevant manuals. It was required to maintain spare parts for this equipment, repair malfunctions within three working days, and audit repaired equipment within five working days. There were also provisions for visual monitoring in the event of a transmissometer failure. The facility was required to retain records relating to self-monitoring, and report observations of visible emissions to the agencies.

Total civil penalties were $1.75 million, one half payable to EPA and the other half payable to the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s Clean Water Fund ($250,000) and the Allegheny County Health Department Clean Air Fund ($625,000). (The action also involved alleged violations of the Clean Water Act). The Consent Decree does not apportion EPA’s civil penalty according to air or water.

Source: Consent Decree dated November 6, 2012:

5. Allegheny County Consent Order and Agreement (April 8, 2014)

In 2013, the Allegheny County Health Department issued a series of Notices of Violation to the facility regarding alleging violations of visible emissions requirements in the county regulations. These alleged violations related to the operations of charging, charging ports, door areas, offtake piping, soaking, pushing, venting or flaring raw coke oven gas.

With respect to compliance requirements, the facility was required to complete repairs to areas of the pushing emission control shed, submit and implement a Baghouse Maintenance Plan, and install a shed extension to minimize the opening between the quench tower and the main shed. It was also required to observe and record the opacity of fugitive pushing emissions, to be evaluated for compliance with county opacity standards. The facility was also required to submit and implement a Charging Procedures Work Plan

The company was required to pay a civil penalty of $300,000, and spend an additional $300,000 as part of a Supplemental Environmental Project designed to enhance particulate collection efficiency at the Battery S-1 quench tower.

6. Joint Motion to Amend Consent Order and First Amendment to Consent Order (September 5, 2014):

In September 2014, the parties amended the April Consent Order. The amendment incorporated the terms and conditions of the 2012 Consent Order. It required the combustion of coke oven gas from the bleeder stacks through a bypass bleeder stack flare system. It modified the procedure for determining compliance with pushing opacity standards. Finally, it required the completion of the requirements relating to the Supplemental Environmental Project, as a condition for termination of the April Consent Order.

7. Group Against Smog and Pollution, Inc. v. Shenango Incorporated (2014-2016)

On May 8, 2014, the Group Against Smog and Pollution commenced an action against the operator of the facility in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania. The environmental organization alleged that the facility had violated several county regulations relating to visible emissions from the coke oven facility. There were three counts in the Complaint.

Count I alleged that the facility had violated limitations on visible emissions from door areas of coke oven batteries, set forth in Section 2105.21.b.1.

Count II alleged that the facility had violated limitations on visible emissions from a coke oven battery’s combustion stack, set forth in Section 2105.21.f.3 and Section 2105.21.f.4.

Count III alleged that the facility had violated limitations on the sulfur content of the facility’s flared, mixed, or combusted coke oven gas, set forth in Section 2105.21.h.3.

The District Court granted the company’s motion to dismiss, under the rationale that a citizen suit may not proceed where the agency is “diligently prosecuting a civil action in a court of the United States or a State to require compliance with the standard, limitation, or order….” See Section 304(b)(1)(b) of the Clean Air Act.

On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed the judgment. It held that “when a state or federal agency diligently prosecutes an underlying action in court, the diligent prosecution bar will prohibit citizen suits during the actual litigation as well as after the litigation has been terminated by a final judgment, consent decree, or consent order and agreement.”

In addition, the Court held that “when a state or federal agency diligently pursues an ongoing consent decree that may be modified by the parties and enforced by the agency, the diligent prosecution bar will prohibit citizen suits.”

Despite the Court’s holding, it does not foreclose all citizen suits simply because a facility has a consent order. The premise underlying the Court’s holding is that an agency is “diligently prosecuting” an action. Whether a prosecution is diligent may involve questions of fact and law. In addition, it is presumed that the agency prosecution and the citizen suit have to involve the same facts, for the diligent prosecution bar to apply.