This section provides an analysis of the federal regulations applicable to coke oven emissions, and highlights their shortcomings in the protection of public health.

Section 112 of the Clean Air Act requires EPA to set National Emission Standards for Hazardous Pollutants (NESHAPs) for categories of industrial facilities emitting hazardous air pollutants (HAPs). The statute contains a long list of hazardous air pollutants, including benzene, ethylbenzene, and xylene (BTEX chemicals), which are emitted by coke ovens. But the statute also defines “coke oven emissions” categorically as hazardous air pollutants.

Under this legal authority, EPA has developed three standards for coke oven operations.

1. “Benzene NESHAP”: 40 CFR part 61, subpart L (for coke by-product recovery plants)

2. “Battery NESHAP”: 40 CFR part 63, subpart L (for coke oven batteries)

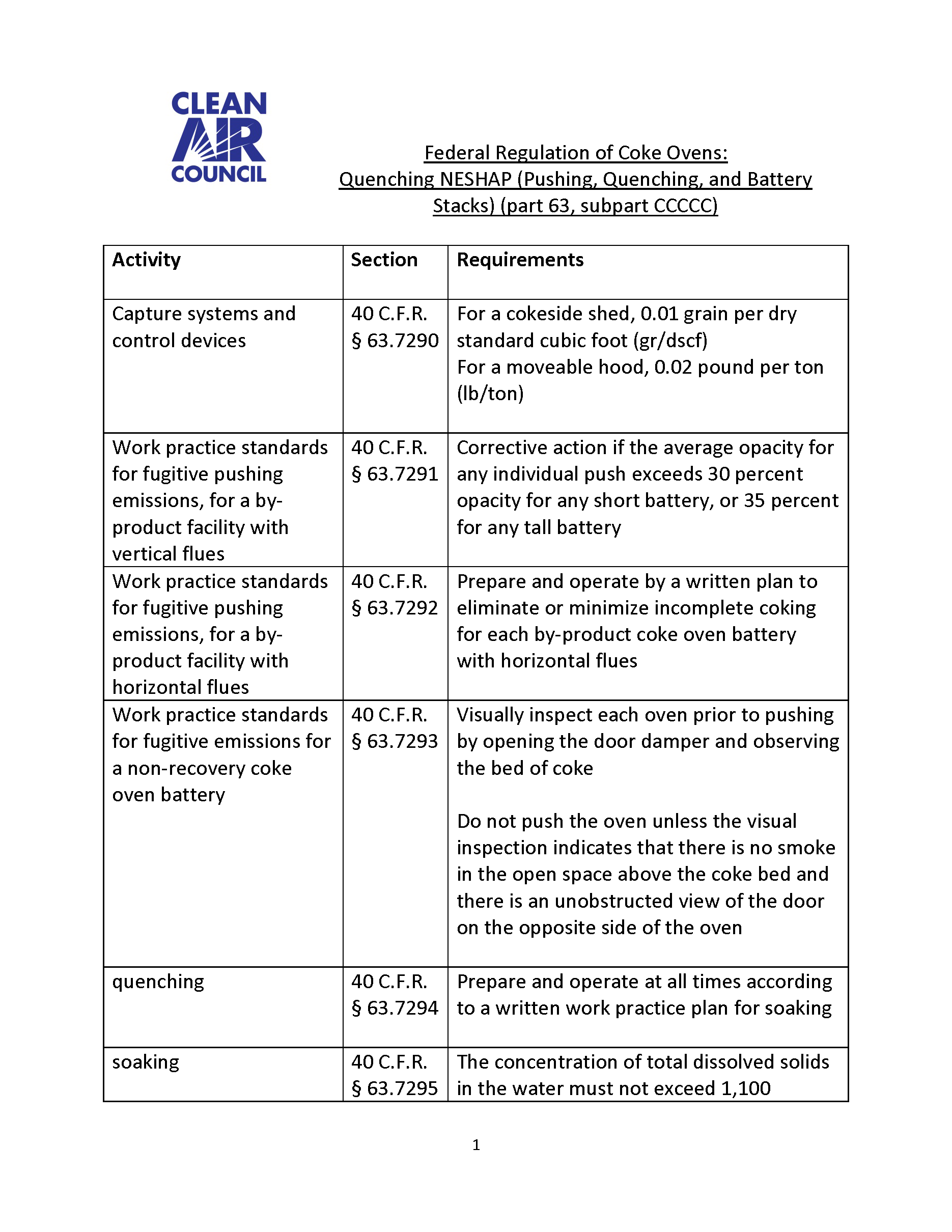

3. “Quenching NESHAP”: 40 CFR part 63, subpart CCCCC (for pushing, quenching, and battery stacks at coke ovens)

These standards require coke facilities to employ the Maximum Achievable Control Technology (MACT) to reduce emissions of hazardous air pollutants. While this is considered the most stringent level of technology control in the federal Clean Air Act, EPA’s standards for coke ovens are flawed by a number of loopholes.

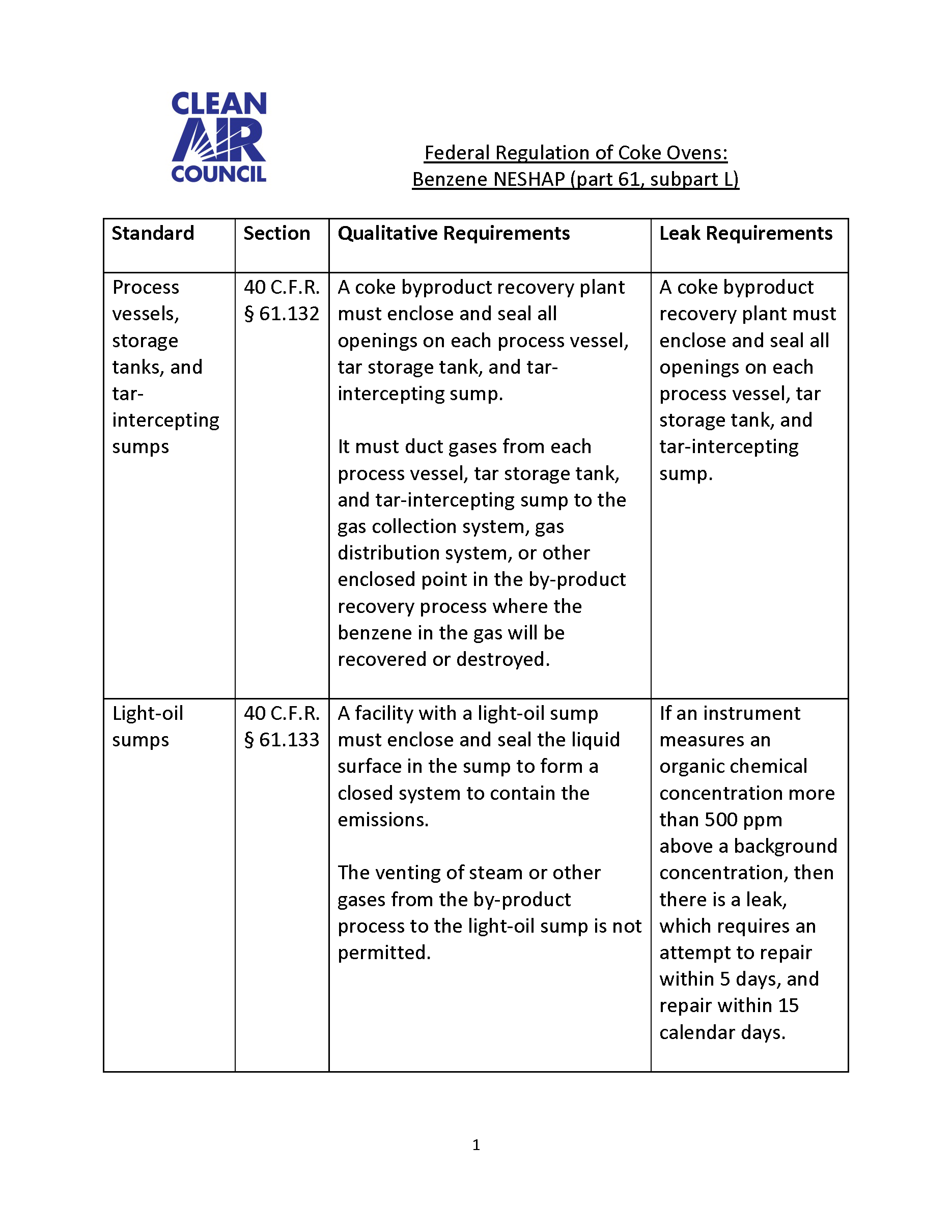

Typically, a MACT standard represents a numerical emissions limitation (for example, x parts per million of a particular pollutant, based on a particular control technology such as a baghouse). To the extent the coke oven standards involve emissions limitations, they are relatively weak.

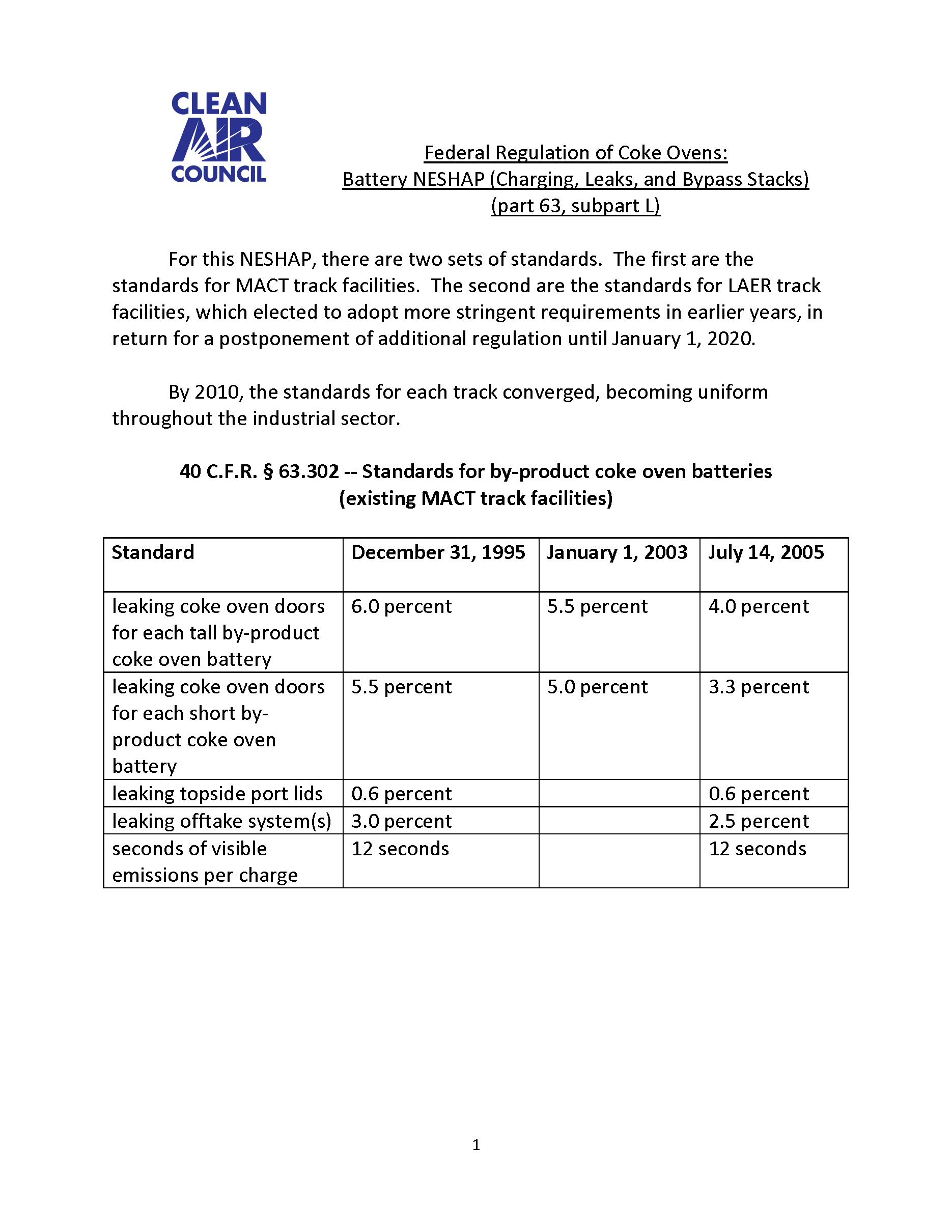

By allowing a certain percentage of leaking doors, topside lids, and offtake systems from coke ovens, the standard is based on a tolerance for defective equipment, rather than on a stringent control technology.

While corrective actions are generally required for leaks, the regulations allow for the existence of significant emissions before a leak is determined.

Some of the emissions limitations are based on opacity standards, which are a relatively weak form of regulation. Essentially, an opacity standard prohibits an air emission only if it is thick enough to be noticeable at a distance. This allows for significant amounts of air emissions to go unregulated.

By 2010, all coke ovens were subject to the same standards under the Battery NESHAP (the standard for charging, leaks, and bypass stacks). However, the LAER track facilities (including coke ovens in Southwestern Pennsylvania) were able to postpone additional federal regulation from 2010 to at least January 1, 2020. By contrast, EPA must conduct a risk and technology review every six years for other regulated industries.

Click here for a detailed analysis of the history of EPA’s regulatory approach to coke ovens, and how it is flawed:

Fact Sheet: Federal Regulation of Coke Ovens under the NESHAP Program

Click the following links for detailed summaries of substantive requirements:

1. Benzene NESHAP (part 61, subpart L) (summary of standards, regulatory sections, qualitative requirements, and leak requirements).

2. Battery NESHAP (Charging, Leaks, and Bypass Stacks) (part 63, subpart L) (summary of evolving standards for existing MACT track and LAER track facilities).

3. Quenching NESHAP (Pushing, Quenching, and Battery Stacks) (part 63, subpart CCCCC) (summary of standards, regulatory sections, and requirements).